Injuring Eternity

As if you could kill time without injuring eternity. —Thoreau

As if you could kill time without injuring eternity. —ThoreauDear Rachel,

Last week on my way home from work I ended up stuck behind several cars at a traffic light. (In Nebraska, this constitutes a “traffic jam.” Remember those traffic jams in L.A. and San Diego? You and I have been in some real traffic jams, haven’t we?) At any rate, the “traffic jam” meant that I had a few moments to just sit there in peace.

As I was waiting for the light to change, I noticed a young woman and her eight- or nine-year-old son coming out of the public library on the corner. I could tell by the set of the woman’s chin and her pursed lips that she was angry about something. She stomped down the walkway toward the parking lot with her shoulders hunched and her eyes flashing. Behind her, the son tried gamely to keep up. Every once in a while he’d say something, looking as plaintive as possible. (And a small boy can look very plaintive indeed.) The mother would glance over her shoulder and snap something back and then continue striding angrily toward her car. Obviously, they were having “issues.”

The whole exchange took maybe 20 seconds or so, just long enough for me to notice what was going on and to wonder what their disagreement might be about. Did the boy take too long while looking at some books? Did he drop a book and break the spine? Did he forget his library card at home, causing his mom to have to turn around drive back to retrieve it? Did he leave a book—now overdue—on his nightstand?

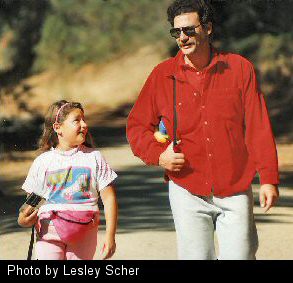

Whatever it was that caused the conflict, it couldn’t have been all that momentous. I wanted to jump out of my car, rush over there, and grab the woman and shake her by the shoulders: “What’s wrong with you?!” I would have cried. “Don’t you know how precious this time is that you have with your son? How valuable? Do you know that, once spent, this time can never be lived again? Is this how you want to spend your time with your son? Angry about some silly, meaningless thing? You should be walking by his side, his small hand in your larger one, and you should both be smiling. You should make sure he’s smiling, because—believe me, I know—it could be the last smile you ever see from him.”

“My daughter’s dead,” I would have said. “She was taken from me suddenly. I would give anything, anything at all, to see her smile just one more time. To walk beside her one more time.”

“But I’ll never again see her smile, never walk beside her. Never hold her hand. You can, though, if you will. Will you? Please? Will you do that for me and for all the parents who, for whatever reason, are unable to walk beside their children?”

Love,

Dad

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home